(Editor’s note: Although the race has been postponed until this fall because of the coronavirus pandemic, this weekend was the original race date for the 2020 running of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and thus makes the 25th anniversary of Chrysler’s Patriot dreams.)

Remember the Chrysler Patriot?

We do, and it was either one of the greatest publicity stunts in automotive history or an expensive but failed experiment in the application of space-age technology to the paved portion of this planet.

The Wall Street Journal suggested the project had the potential to “push (the) search for electric vehicles in a different direction.”

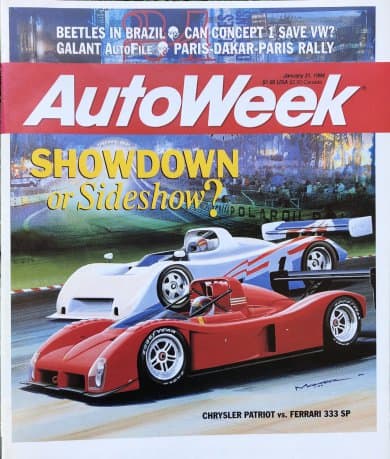

In its cover story, AutoWeek magazine suggested the car’s success might finally answer the automotive age-old question: What justifies all the money and time, not to mention the risk of life and limb invested in motorsports? Is it marketing or is it technology?

You may not remember the Chrysler Patriot, the car that was going to revolutionize not only auto racing but automotive power period, but I do. I wrote that AutoWeek cover story.

Looking back, it seems we had our doubts. “Showdown or Sideshow?” was the headline on the cover of that January 31, 1994, issue.

The Patriot had been unveiled earlier that month at the North American International Auto Show in downtown Detroit. The stated goal was to enter the car — and its revolutionary, truly space-age powertrain — at the Daytona, Sebring and Le Mans endurance races in 1995.

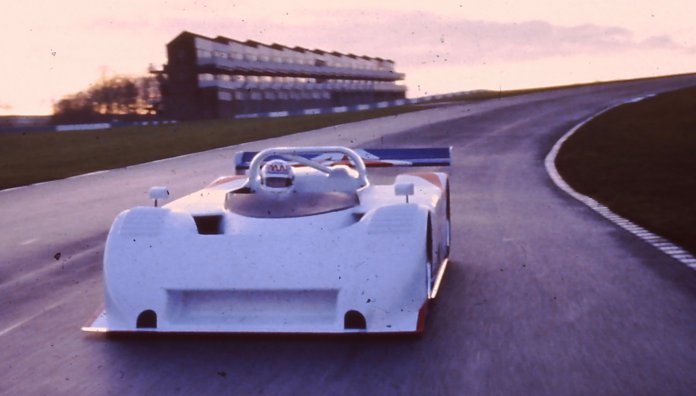

At the time, and again a few months later at an in-depth Patriot technology update press session at Chrysler’s secretive Liberty research and development “skunkworks” facility north of Detroit, we were told Patriot already had done “shakedown laps” around the Donington Park race track in England. There were even photographs and video of that test session.

Problem was, as I would learn, though not until a year later when I chatted at a sports car race with Andy Wallace, the “driver” shown occupying the car for those shakedown laps, what we were not shown was Wallace grasping a tow rope as he and the Patriot were being pulled around the track behind a truck. Once up to speed, and on downhill sections of the track, Wallace was signaled to release the rope and to steer the car as though it was operating under its own power instead of — in reality — the power of inertia and gravity.

As it turned out, the ultra-high-speed flywheel technology that provided power for satellites operating in the gravity-free environment outside the earth’s atmosphere (and for submarines in the depths of the oceans) apparently could not be made to function as well in a ground-bound race car.

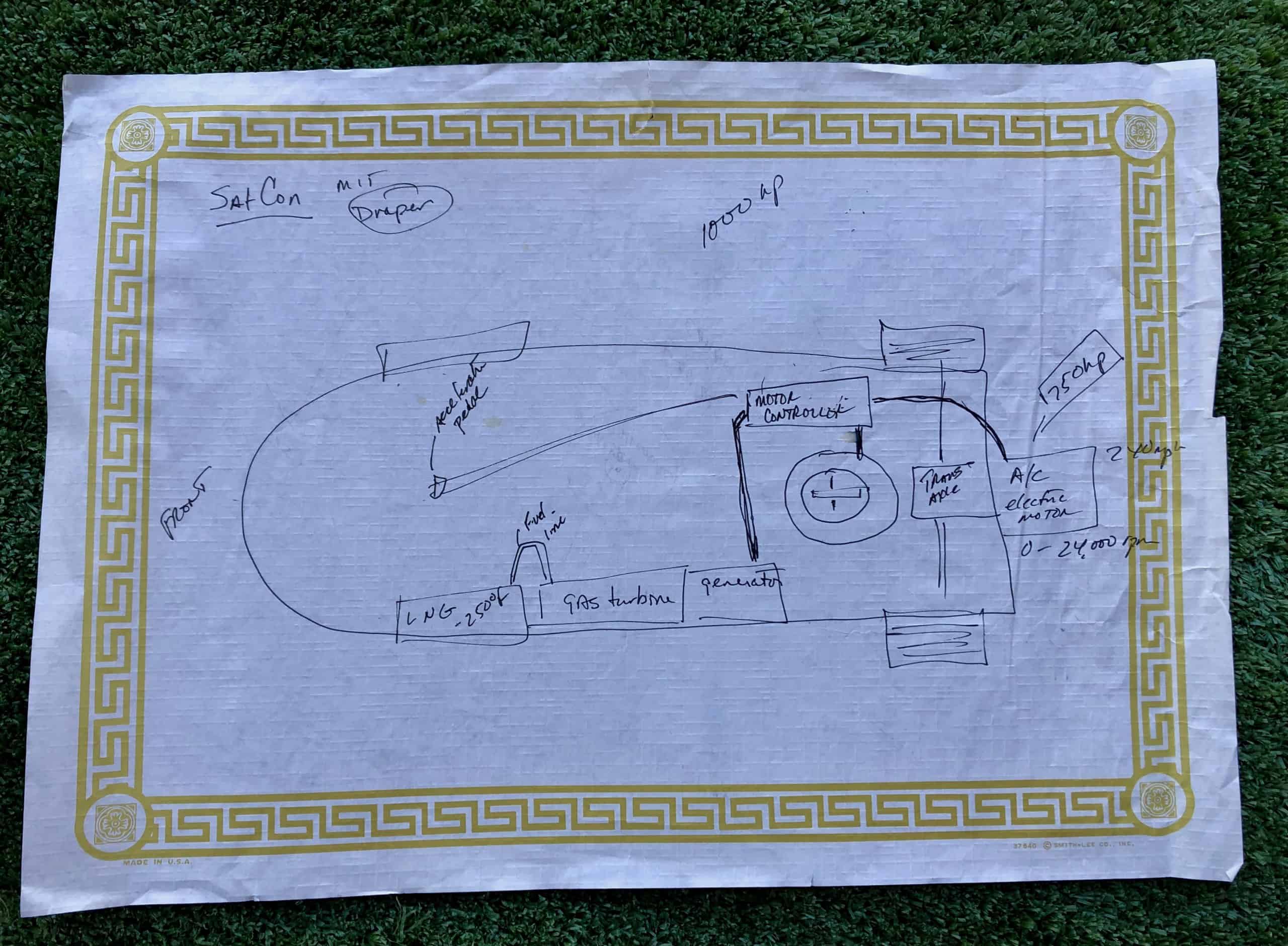

Of course, that’s not what we were told at the auto show, nor at the press briefing six months later. At the briefing, a parade of engineers from Chrysler and its affiliates, which included the likes of Westinghouse Electric, Satcon and Cryogenics Experts Inc., talked about the various components of the revolutionary automotive powertrain that was being developed.

It also was revealed that the car itself had spent nearly 170 hours in wind-tunnel testing and was being revised into a Mark II chassis that would be used for actual powertrain testing.

It would be another six months, and after some apparently actual powertrain development, before Chrysler admitted to issues with the flywheel, the traction motor, the power controller, the fuel system and with other components of the Patriot’s proposed hybrid powertrain.

Chrysler did reveal at least one of those issues, that the natural gas-fueled turbine involved in the powertrain was spinning so fast that it generated so much heat that its blades were melting.

The Patriot powertrain was to link a 24,000-rpm traction motor/controller and a 100,000-rpm two-turbo/alternator to a 58,000-rpm flywheel housed in a carbon-fiber housing rated to contain forces up to 920,000 ppi. The flywheel would act as a mechanical battery, storing power until it was needed to provide “sudden” acceleration.

Such a system, Chrysler said, not only had environmental benefits, but had potential to influence automotive technology in the next century and the U.S. government’s desire for a “car of the future” program. Chrysler also said it wanted to return to major international racing and had considered Indianapolis and Formula 1 as well as sports car racing. Racing, it added, provides a laboratory for developing and evaluating technology while inspiring engineers to strive for ways to win.

“Back 40 years ago, motor racing helped invent such things as disc brakes and fuel injection, as well as other technologies which helped safety and emissions,” Chrysler vice president Francois Castaing had said at the Detroit auto show in 1994.

“Well, we at Chrysler believe that racing should be brought back to this original purpose.”

He also said that automakers divided their engineers into groups. For example, “the ‘green’ guys” and those who “do performance.”

“But who says we can’t combined them?” he said. “And where is it written that a vehicle that is ‘green’ can’t also be ‘red-hot’ with excitement?

“If we are successful,” he added, pointing to the Patriot plan for a car burning natural gas in a hybrid system producing more than 500 horsepower and speeds in the range of 200 mph, “we will prove that efficient and clean vehicles of the future do not need to be boring to drive.”

He was right, though the technology wasn’t proven by Chrysler’s Patriot but by Formula One racing teams using flywheel-battery setups as part of their energy recovery systems.

And, as it turned out, Chrysler did race at Le Mans in 1995, just not with the Patriot. Instead, it was with Dodge GTS-R Vipers, the best of the bunch finishing 10th overall, though 34 laps behind the winning Porsche prototype, and only 8th in the GT1 class.

If you really wish to to know what happened on the Patriot project you need to talk to Ian Sharp the proposer, concept initial designer, (not this thing that spewed out of the corrupt Corporate wringer) and the $82M Government maleficence (Tax Payer) that took place on the project after I left. See my Linkedin profile with the attached RaceTech article….